At the time of writing Ding Junhui has just won his 4th ranking title of the 2013/14 season, the German Masters in Berlin, and there are still 5 more ranking events to go. This has only been achieved once before, way back in the 1990/91 season when Stephen Hendry – fresh from his first world title the previous season – won 5 ranking tournaments. Funnily enough it was the only season he didn’t win the world title between 1990 and 1996.

When Ding burst onto the scene winning the 2005 China Open the day after his 18th birthday defeating none other than the then world number 3 Stephen Hendry in the final, he seemed destined to become the next dominate force in the game, and fast. Later that same year he picked up his first UK title and went on to become only the second teenager after John Higgins to win 3 ranking events when he defeated Ronnie O’Sullivan in the final of the 2006 Northern Ireland Trophy. He then picked up 3 gold medals in the Asian Games in December 2006 before succumbing to the combined effects of jet lag and exhaustion in losing his UK crown in York a few days later.

The following month in the 2007 Masters he became the youngest player to make a televised 147 (a record still held) and breezed to the final where he faced Ronnie O’Sullivan. Ding took the first 2 frames, but then everything changed. O’Sullivan hit the afterburners and obliterated him with a display of snookering perfection but it wasn’t just that; O’Sullivan has done that to many before and since. What changed was that the automaton suddenly became human.

Until that match nothing appeared to phase Ding, he played as if he was under no pressure, experienced no emotion and was genetically programmed to pot balls. The psychological advantage of being emotionally unreadable unnerved many an opponent and won him matches before a ball had been potted, yet subsequent to the 2007 Masters final opponents realised he was fallible and if they could just get a couple of frames in front, Ding’s head would drop and they had got him.

Poor Ding had lost his way, and no matter what external factors were going on in his life at the time – a young lad feeling isolated in a foreign country with an alien culture to the one he knew, the pressures of being a national icon in his homeland and not delivering the results demanded of him – the end result was that he was not fulfilling his considerable talent and replicating the likes of Stephen Hendry in becoming the dominant player of his generation in his early 20s. The class has always been there with Ding, yet the mental frailties were all too apparent; if things weren’t going his way on the match table he waved the white flag and gave up.

Now at the age of 26 Ding the man, not the boy, appears to have put all this behind him and is starting to produce the sort of mesmerising snooker that sets him apart from every other player of his generation. He has noticeably matured over the last couple of seasons – he doesn’t give up like he once did when the scoreboard indicates he is 2nd favourite for the frame or match – and is close to becoming the finished article. He is currently better than he ever was, and as good as his early promise suggested he would be at this age.

So what is it about Ding that sets him apart? Why do other players rave about him so much?

Ding has a great cue action, there’s not a lot that can go wrong with it and therefore it holds up pretty well under pressure. It’s been described as robotic and to many a casual armchair viewer it seems somehow programmed to pot clean balls every time and is therefore boring to watch. Well more fool them because Ding will obviously practice his cue action through monotonous routines to retain its accuracy and robustness but when all is said and done the cue action is simply the reliable tool at his disposal in order for him to fully explore his mastery among the balls.

Ding has exceptional cue ball control and judgement of pace similar to Ronnie O’Sullivan; he can play a shot at full power sending the cue ball around the table and consistently land it in an area the size of a tea plate. He also has a good tactical game borne out of years of professional match play experience, but he would rather be potting balls than getting bogged down in tactics.

But what really sets Ding apart from the rest is his mastery of cannons and splits. His virtuoso talent in this area enables him to make frame winning breaks which didn’t seem possible when he came to the table, and it also increases his chances of scoring big breaks when he’s in and around the black spot area by limiting any reliance on luck to land on the next ball when bringing reds into play.

The only players in his category when it comes to cannons and splits are O’Sullivan and Hendry so that should say something, and even then in my opinion Ding is even better at this facet of the game. Ding sees things others players don’t, he can work out how a group of balls will split like no other player before him or since. Cannon play is obviously a key factor in the art of break building and in Ding’s case it is evident in pretty much every sizeable break he makes so to demonstrate I’ve chosen his most recent win in the 2014 German Masters final as the example.

Coming in to the final Ding had beaten an in form Ryan Day 6-5 in the semi-final in a memorable encounter, whilst in the other semi-final his opponent Judd Trump had produced a magical display to reel off 6 quick-fire frames against Rod Lawler after losing the opener. The bookies installed Judd as favourite based on his form that week and the fact he had only dropped 4 frames in reaching the final, despite Ding having won 3 ranking finals already this season. Judd started where he left off in compiling a break of 80 in the first scoring visit of the final.

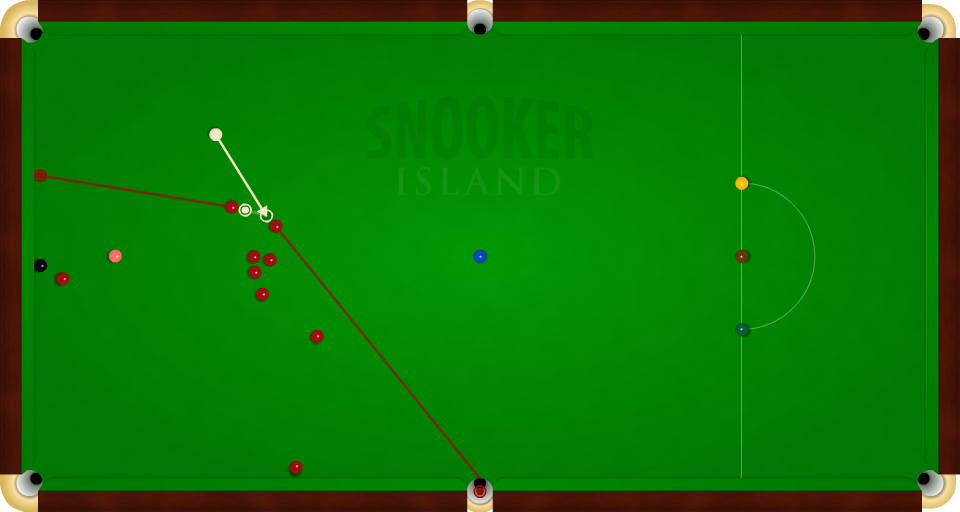

In frame 2 we have the first example. Ding is on a break of 39 and has landed slightly out of position on a red with position to the next colour deceptively tough. The obvious red to take on is red to middle, but how to land on a colour?

Most players would instinctively attempt to screw back for pink to right corner yet the blocking red adds an uncertainty to the shot. If it was possible to screw past this red for pink that’s what Ding would’ve played, but a cannon on this red brings two factors into play, firstly a full cannon by not getting into the white enough would stop it dead in no mans land:

and secondly a glancing cannon would likely bring the red towards pink with a strong possibility it would end up blocking it to right corner:

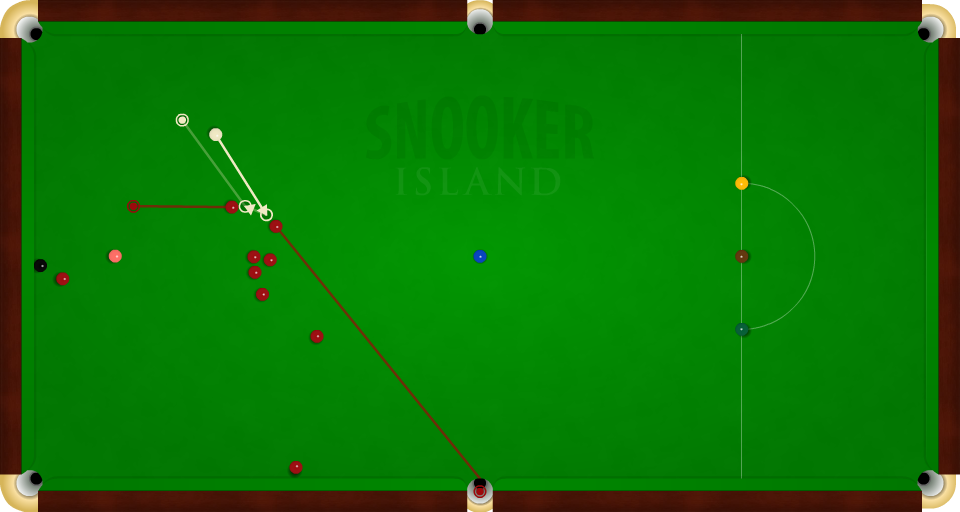

Ding spent a while plotting the next shot, and in the end played with top spin at medium pace using the end red in the bunch to send the white nicely down for pink to left corner, and also opened the bunch of 4 reds into potable positions. It was a frame winner as he went on to compile a break of 87 and level the scores at 1-1. It was also a very difficult shot to judge as well as he did, but this is what Ding does.

The scenario after the frame winning shot:

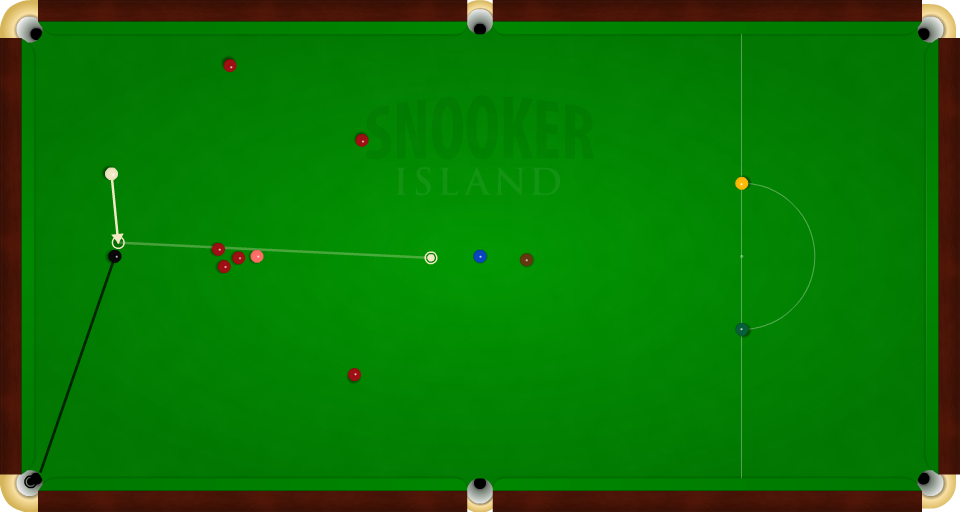

Judd won the next 2 frames to lead 3-1 at the first interval. In the 5th frame Ding was in a position where you would fancy most professionals to make a sizeable break, yet this task was made much easier by a shot he played with the scores at 17-0. There was no pressure on the shot, it was straight forward enough to pot black with the chance to go into the bunch and land on a guaranteed red to corner, yet it was set up perfectly for the shot Ding played which resulted in a choice of easy reds to both middles and corners. He spotted it straight away, screwing directly into the apex red guaranteed to open the bunch most efficiently, and used a 3rd red as a stopper to leave the white in the perfect spot. (The back up reds for next shot highlighted, cue ball path shows pace it hit stopper red)

He played it to perfection and ended up with a choice of easy reds to both middles and corner pockets, and from there it was simply a case of mopping up to pull back to 3-2.

In the next frame with the scores poised at 35-35 Ding again found himself in a spot where there was one red to go at but position to a colour wasn’t obvious. He could have played with top spin to avoid the second red but the white would go dangerously close to the in off and if avoided would likely catch the second red on the way back up and not land nicely on a colour. He chose instead to deep screw directly into the second red on the cushion, using it to bounce off and bring the cue ball back up table for a choices of blue or baulk colour and simultaneously develop the red into open play. He ended up losing the frame but given the frame situation at the time of the shot it demonstrated his thinking and gave him the chance to score more points, and he would have expected to win the frame from there.

Ding took the next to pull back to 4-3 and in clearing to win at the end of frame 7 started a run of 460 unanswered points. In the last frame of the afternoon session he played one of the most spectacular shots of the match. The safety shot back to baulk was the obvious shot at first glance however a good cue ball would be needed in order not to leave an exceptional potter like Judd the chance of a long one to go at, and with it the possibility of taking a 5-3 lead after the first session.

Ding spotted a plant which maybe he thought Judd might take on if he left so why not go for it himself? It was an incredibly attacking shot and the plant was far from guaranteed, but there was method in his madness as he worked out that although the white was going into the bunch, the reds were laid out in a way in which it would be very unlucky not to leave himself a shot on the pink. Certainly the pink wouldn’t move. He played it to absolute perfection with enough action on the white to give it a second wind after initial contact, and he went on to make a break of 81 for 4-4. Psychologically that break may well have won him the final and it all started with the extremely attacking plant. (Cue ball path shows pace and fizz as it went into the reds, next diagram shows what he left and one more shot into prime position)

At the start of the second session Ding knocked in his highest break of the match, a total clearance of 125. When the break reached 10 he landed on the blue and position to next red wasn’t obvious. He could have played one of his favourite shots, to bust the pack open using the pink, but the pink was away from the bunch and he saw something else. He solved the puzzle with a very nice holding cannon on the red to open the path to the next red. The shot required a good touch because it needed the right contact from distance, but he worked out that with the correct pace there was a margin of error in that the cue ball could glance off the pack into the holding cannon, which is what actually happened.

He landed perfectly on the next red, then screwed into the cannon for position on the black pushing the cannoned red towards corner pocket, then used this red as back up when going into the pack from the black and all of a sudden he was away. (Next shot black to corner, white into reds via top cushion leaving at least the open red to corner)

For the subsequent few shots he played a series of holding cannons – nothing too difficult or spectacular but all the while bringing balls into play whilst retaining position. The series of cannons was reminiscent of Hendry who also used full ball contacts or glancing blows on reds when break building to hold the white for the next ball whilst gradually bringing other reds into play with the cannons. This is an art form made to look very easy by the likes of Ding and Hendry, but takes years of practice and a natural touch to master. If you don’t get the cannon exactly right, you lose the cue ball almost every time.

Ding made a 101 break in frame 10 to lead 6-4 followed by a 72 to lead 7-4. During these breaks he didn’t face any challenges or play any cannons of note as the reds were fairly open when the break started, but again this demonstrated his exceptional touch and judgement of pace in not running out of position and always leaving easy shots for himself, thus making the art of break building look very easy.

He won a scrappy 12th frame to lead 8-4 at the last interval, and on resumption had clearly been stewing in the dressing room being just the one frame from victory and having time to think about it. So the remainder of the match saw Ding looking slightly edgy and with the adrenaline running through his veins he lost his touch and was slightly over hitting his shots.

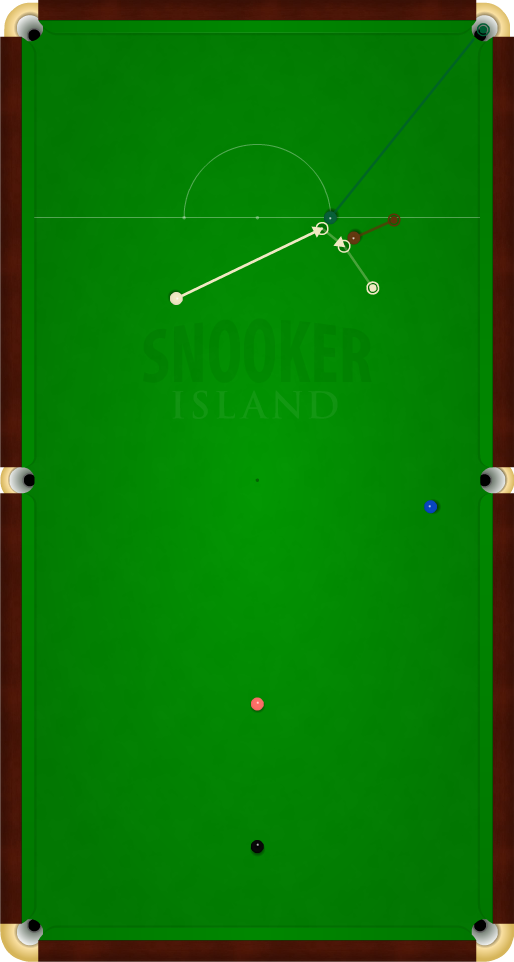

An example of how this affected his cannon play comes at 8-5 and leading 40-8. If the shot goes right he’s won the title, you can see him eyeing up the cannon to left red which would free the pink and 3 reds and guarantee him an easy red to middle at worst, however he uncharacteristically cannoned the wrong red and ran out of position. It was unlike Ding but also shows how easy it is for things to go wrong when you don’t get the cannon exactly right.

The intended cannon (of course the cue ball wouldn’t travel more than a couple of inches after catching the cannon left of centre, the line shows ideal pace and direction):

The execution:

He landed on nothing due to the poor execution. On another day he may have landed nicely on a red but more through luck than judgement. From here he took on red to yellow pocket but missed and let Judd in for a counter attack.

He handed Judd a lifeline but after doing all the hard work and getting himself in position for an easy out to pull back to 6-8 Judd missed a straight blue to middle to give Ding the chance of clearing from yellow to pink for the title.

Ding played yellow with extension, stretching rather than using the rest (again, demonstrating the enormous pressure he was feeling) which lead to him landing deceptively awkward on the green. He intended to land straight behind the green which would leave a simple screw back for easy brown to blue. Given the enormity of the situation how many players would’ve had the clarity of thought to play the slow cannon onto brown using drag to leave an easy straight pot to corner for guaranteed position on the blue? For Ding it came as second nature; he spotted the shot immediately and duly cleared to pink for the title.

If you would like to see the shots talked about in this blog, the final is on YouTube.

Next time you watch Ding in action, keep an eye out for the subtle cannons he plays and when he opens the reds, watch how often the split works out for him. If he spends a while thinking about the next shot, see if you can work out what he’s going to do because the chances are it will be something different, and it will be inventive and it will open the table up for more points to be scored. When Ding is in full flow he is mesmerising to watch, the shots described above are merely the tip of the iceberg; there’s plenty more where they came from and they are to be found in every single match he plays, every sizable break he makes.

Some still question his temperament which seems absurd given all he’s won in the game, but until he wins the World Championship a small section of the snooker public will remain sceptical of his chances to do so. I for one have no doubts whatsoever that one day he will lift that title, and Ronnie O’Sullivan aside he has to be the favourite to do so this year. Maybe he is the only man capable of stopping O’Sullivan, we’ll just have to wait and see but in the mean time who is going to bet against him equaling and then surpassing Hendry’s 5 ranking titles in one season?